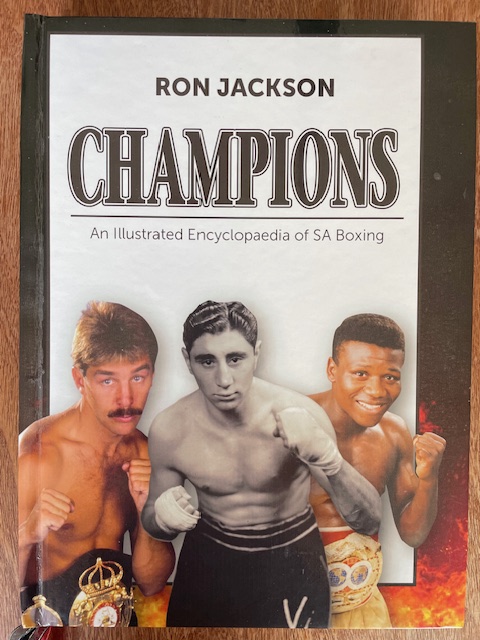

The first of a new feature of regular articles by esteemed South African boxing writer and historian Ron Jackson.

Famous old fight venues in London and South Africa

In the early years of British boxing there were many famous venues in London and amongst them was the famous Blackfriars Ring which was bombed down to the ground in the Second World War during the Blitz in October 1940.

The Ring was built as a Surrey Chapel in 1782 for the evangelical preacher Reverend Rowland Hill, and in the late 19th century it was occupied by an engineering company, and from 1910 it was used as a boxing venue.

The first fighter in The Ring in Blackfriars Road, Southwark back in 1783 was Reverend Rowland Hill who originally designed the building as a church so that he could fight the devil.

It is reported that that the unusual, circular design was that there would be no corners in which the devil could hide.

Many years later Dick Burge a former English middleweight champion was responsible for overseeing the chapel’s conversion to a boxing venue.

With his wife Bella’s support he rented the old circular chapel, which had fallen into disrepair and used as a warehouse.

Dick and Bella enlisted homeless people who cleaned out the building so that it could be used for boxing, which they opened on 14 May 1910.

Only four years after The Ring opened, The Great War erupted, and Dick enlisted but sadly he contracted pneumonia in 1918 and died shortly before the war ended.

However, Bella continued to run the boxing venue and she became the world’s first women boxing promoter.

In the late 1930’s with the clouds of the Second World War looming she ran into financial difficulties before the destruction of the venue.

Bella died at the age of 85 in 1962.

The bombed site was left abandoned until the 1960’s when a modern office block was built on the site, but by 1998 became derelict and replaced with modern building.

Right across the road where the original boxing arena stood is a pub named The Ring which hosts a collection of boxing memorabilia on its walls.

London also had several other famous boxing venues like The Harringay Arena, which was situated near Manor House, the scene of the first Freddie Mills vs Gus Lesnevich world light heavyweight title fight on 14 May 1946, with Mills being stopped in the tenth round. The arena could hold 11500 fans.

It was an almost ideal venue for boxing with banked terraces of seats surrounding the ring and above the ring were four huge clocks which timed the three-minute rounds and the one-minute intervals.

The old Wembley Arena holding 12500 fans was another wonderful structure with every spectator having a clear view of the ring. The only drawback was that it was situated on the outskirts of London.

The Empress Hall at Earl’s Court was also a fine venue for boxing, holding 10000 all under cover.

The Olympia was also a popular venue and the famous Royal Albert Hall with its lower and upper circles has been used for boxing until recently.

In London there were several other stadiums where big fights were held, including the White City Stadium and Wimbledon.

In many of the halls the seating was under cover and permanent so that that it would not involve the hiring of chairs other than transporting the ring and other appurtenances, which had to be done at the old Wanderers Stadium in Johannesburg when boxing was the home of all big fights in South Africa.

Possibly the most famous boxing small hall is the York Hall in Bethnal Green situated on Old Ford Road which was opened in 1929 and is still in operation today.

In South Africa there have also been some memorable boxing venues like the Wembley Stadium in the south of Johannesburg which also included a speedway track.

In one of the biggest fights in the history of South African boxing the popular South African heavyweight champion Johnny Ralph was knocked out in the eighth round by the world light heavyweight champion Freddie Mills on 6 November 1948 at the Wembley Stadium.

The stadium was subsequently demolished and is now used as a bus depot.

Close by is the Wembley Indoor Arena in Turfontein Road which was formerly known as the Olympia Ice Rink where many famous fights were held.

Another popular venues in later years was the Ellis Park Tennis Courts in Johannesburg.

Tournaments were also held at the Johannesburg City Hall and smaller tournaments were held at the Selbourne Hall, and Drill Hall.

Amongst the other venues are the Uncle Toms Hall, Kwa/Thema Recreation Centre, Sebokeng Community Centre, and the Mdantsane Indoor Centre (East London), Feathermarket Hall (the then Port Elizabeth), Portuguese Hall, Durban Ice Rink and the Nasrec Indoor Arena.

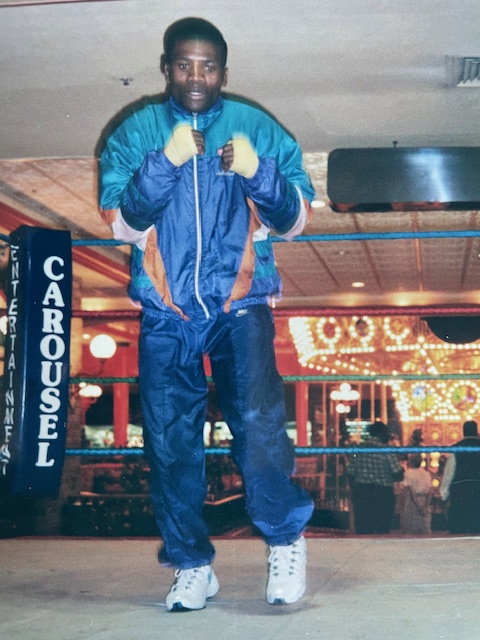

Promoters also used the Durban, and Cape Town City Halls and on 29 April 1995 South Africa’s Vuyani Bungu who holds the record for the number of world title defences by a South African retained his IBF junior featherweight against Victor Llerena at the iconic FNB Stadium.